By Dan Barry

The sound of the bugler calling for assembly echoed, wreaths were placed, a choral group performed, and officials gave speeches, all atop a hallowed hill in Gettysburg, Pennsylvania. This was part of the remembrance for the 161st anniversary of the address that has come to define the essence of being presidential.

On November 19, 1863, at this very site, President Abraham Lincoln, standing tall at 6 feet 4 inches, dedicated a national cemetery for soldiers, made necessary by the devastating Battle of Gettysburg just months before. His 272 words transformed into a civic prayer for unity and purpose amidst a nation torn apart by civil war: the Gettysburg Address.

Now, precisely two weeks subsequent to a divisive presidential election that seemed to deepen the national divide, a Lincoln scholar named Harold Holzer was honored to channel the 16th president and recite his timeless words. He too bore a beard but was raised in New York City’s borough of Queens, not the forests of Kentucky, and stands at about 5-foot-9.

Holzer was intimately familiar with the address, nearly as much as he knew the Shema, the Jewish prayer. Nevertheless, he had anxious thoughts in the days leading up to this event. “I don’t possess the voice for it,” he had confessed.

The timing of the gathering, so soon after the elections that had re-elected a controversial president, weighed heavily on Holzer, who reflected on how dramatically the perception of “presidential” had shifted from then to now. Between a leader known as “Honest Abe” and a man with 34 felony charges; from one who called for “the better angels of our nature” to one who insulted his rival as “retarded” and labeled undocumented immigrants as “poisoning the blood of our country.”

“Heartbreaking,” was Holzer’s remark.

On that distant 1863 day, similar in mildness to this day, Lincoln and other dignitaries gathered on a creaky wooden platform at the cemetery’s edge. Reminders of the three days of intense bloodshed in July, resulting in over 50,000 casualties, surrounded them. The bullet-riddled buildings, cannon-scarred fields, and roadside souvenirs made of shell fragments evidenced the town’s transformation, which had left many dead and dying soldiers to contend with.

Lincoln’s invitation to provide “a few appropriate remarks” had originally been an afterthought. Edward Everett, a well-known orator, had been selected to deliver the keynote, and when the moment came, he spoke for nearly two hours, filled with classical references and elaborate sentiments.

Then came the president, marked by the ravages of war and the loss of a beloved son, who faced ridicule for his mannerisms. He rose and began — “Four score and seven years ago” — completing his remarks in roughly two minutes. He returned to his seat, feeling his brief speech had fallen flat.

Now, a short distance from where Lincoln had stood, Holzer found himself seated with other esteemed guests on a bunting-decorated platform, gazing at several hundred attendees in folding chairs as white as the tombstones in view. Most attendees wore casual clothing; some donned Civil War-era garb; at least one sported a MAGA hat.

Holzer opted for a tweed jacket, gray pants, and layered long johns beneath. Having participated in numerous annual events organized by the Lincoln Fellowship of Pennsylvania, he was well aware of the November winds blowing across the solemn grounds.

Throughout his 75 years, he had taken on many roles: reporter, press officer for former New York Governor Mario Cuomo, museum executive, and currently director of the Roosevelt House Public Policy Institute at Hunter College in Manhattan. He had authored and edited over 50 books, nearly all focused on Lincoln and his time, and — upon reflection, he no longer felt anxious.

However, before Holzer could step up to the lectern, a customary part of this event had to occur. Sixteen individuals from eight nations — Bhutan, Britain, the Dominican Republic, Ghana, Guatemala, India, Mexico, and South Africa — stood united.

They raised their right hands. They renounced allegiance to any “foreign prince, potentate, state or sovereignty.” They pledged to protect the Constitution. They affirmed their loyalty to the United States of America.

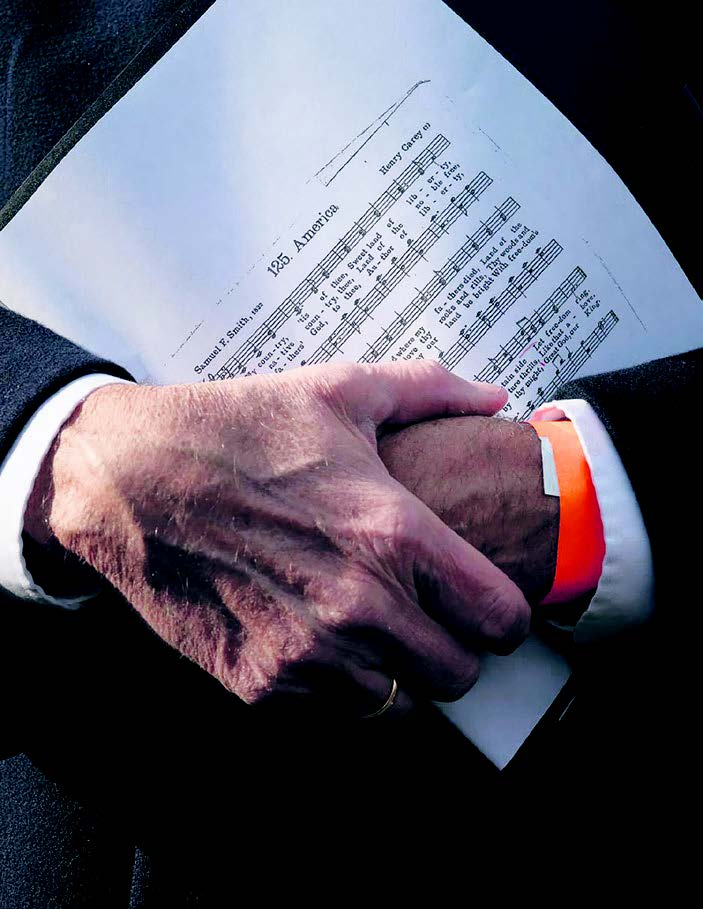

With that, a representative from the U.S. Citizenship and Immigration Services welcomed “our newest citizens” to cheers and applause. The Gettysburg Area High School Ceremonial Band began playing “America the Beautiful,” while gray-haired Daughters of the American Revolution distributed red-white-and-blue keepsakes and copies of the Constitution.

Among these new Americans was Hugo Lara Barajas, a truck driver and crane operator originally from Mexico. During the event, his wife, Monceratt Moya, watched their infant, Araceli, while their other children, Anastasia, age 6, and Joaquin, age 3, played on the grass with a small American flag souvenir.

“I’ve anticipated this for a very long time,” Barajas later shared. “Now I’ve attained the right to vote.”

The scene, a beautiful combination of solemnity and celebration, deeply touched Holzer, a grandson of Eastern European immigrants. With a pen in hand, he added a few words to his introductory notes.

Now the moment had arrived. Called to the lectern, Holzer opened his notes. He stated that the words he was about to read represented “sacred American scripture,” adding that to him, “this address, this elegy, has never felt more poignant, more relevant, or more vital than it does today — a time when it appears not merely as a relic of history, but as a prayer for the future.”

Then, reading what he had just written, the Lincoln scholar spoke to the newest citizens: “Regardless of what you might have heard or will hear — words that may sound chaotic, or hurtful — this is the true voice of America.”

He commenced: “Four score and seven years ago our forefathers created a new nation on this continent, conceived in liberty, and dedicated to the proposition that all men are created equal.”

As Holzer recited, gradually and seamlessly, the biblical rhythm of Lincoln’s straightforward language cast its entrancing influence. The words and imagery, entwining the specific battle of Gettysburg and the ideological struggle for equality, resonated significantly, especially given the nearby stones that marked the graves of thousands who sacrificed their lives for national unity, many of them forever labeled as “unknown.”

The only sounds were his voice. Some bowed their heads.

“That we here highly resolve that these dead shall not have died in vain — that this nation, under God, shall experience a new birth of freedom — and that government of the people, by the people, for the people, shall not disappear from the earth.”

Holzer then sat down. Silence lingered.

“The Battle Hymn of the Republic” was performed. A prayer of blessing was offered. And the bugler played “Taps.”