By Katie Glueck

In Ohio, Sen. Sherrod Brown, a persistent advocate for working-class constituents, faced defeat at the hands of a wealthy Republican ex-car dealer.

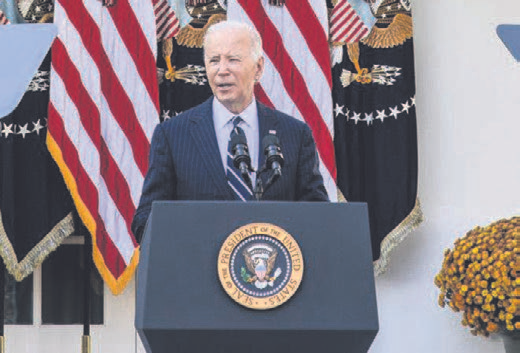

In Washington, President Joe Biden — who clinched the Democratic nomination four years ago thanks to support from blue-collar voters — is now compelled to return authority to Republicans and relinquish control of a party increasingly influenced by well-educated voters.

And in Pennsylvania, Sen. Bob Casey, a name long tied to white working-class Democrats, is facing a legitimate chance of losing.

Eight years after discontent among white working-class voters led to Donald Trump’s election, Democrats promised to improve their rapport with that demographic this time.

However, the party’s considerable difficulties with blue-collar voters have only intensified. Widespread dissatisfaction with soaring prices and disconnect from Democrats have turned the party’s representatives in Trump-leaning areas into increasingly scarce entities.

“When expectations for change fail to materialize, hope transforms into anger,” remarked Rep. Matt Cartwright, a seasoned Pennsylvania Democrat from the Scranton region who narrowly lost in this past election. “And that anger was evident.”

Trump’s new foothold with working-class voters of color, especially among Latinos, has raised alarms within the Democratic Party. Simultaneously, the party’s Achilles’ heel from the Trump era — its struggle to gain the trust of white working-class voters — has become even more pronounced this year, particularly in the Industrial Midwest, where the traditional Democratic strongholds of Michigan, Pennsylvania, and Wisconsin all leaned toward Trump.

In many blue-collar counties in those states, Vice President Kamala Harris experienced larger losses than Biden did in 2020.

Certainly, several Democratic candidates for House and Senate outperformed Harris. She also faced numerous political hurdles that Biden did not encounter four years earlier, including issues of racism and sexism, along with the significant complication of conducting a 107-day campaign following the withdrawal of the unpopular president.

However, she and her fellow Democrats also grappled with a growing and troubling perception issue: a widespread sentiment among working-class Americans that the Democratic Party fails to comprehend their challenges — and in some instances, outright scorns them.

“This doesn’t necessarily spell the end for white working-class Democrats,” stated Justin Barasky, a Democratic strategist who managed Brown’s 2018 campaign. “But it certainly will if we don’t take steps to be more inclusive.”

Battling over language and cultural issues

Democrats have been candid in diagnosing the reasons behind their significant defeats.

Voters, disillusioned by inflation during the pandemic and concerned about the migrant crisis, reacted against the ruling party. Republicans effectively painted Democrats as excessively liberal and “woke.” Democrats needed a more assertive populist approach.

Misinformation thrived in a fragmented media landscape. The nation simply wasn’t prepared to elect a woman, particularly a woman of color.

There is some validity to these various theories, according to Democrats who have examined the political landscape in blue-collar America.

However, one of the primary issues, these Democrats argue, is that voters in predominantly white working-class neighborhoods now perceive the party as unresponsive to their most urgent, everyday concerns.

Rep.-elect Kristen McDonald Rivet, D-Mich., secured a district inhabited by many white working-class individuals, despite Harris struggling in numerous counties there.

McDonald Rivet stated that for many voters in her region, rising costs were not merely an inconvenience but a source of “fear about their ability to get by,” she remarked.

For those voters, she noted, discussing other topics — whether Trump fits the label of “fascist,” for example, or the events of the Capitol riot in 2021 — felt less pressing.

“Those types of discussions don’t influence their day-to-day experiences,” she explained. “It boils down to the price of a gallon of milk.”

To some extent, voters conveyed in interviews this year that Trump gained from a sense of nostalgia for the pre-pandemic period — while the disorder of his former administration faded from memory for some.

“I’m not fond of the Democrats’ rhetoric,” declared Jeff Markey, 66, a former airport technician from Wyoming, Michigan, a more working-class city near Grand Rapids. He mentioned that he had backed Democrats until Trump’s candidacy in 2016, and supported him again this year.

“I appreciated how secure the nation felt during Trump’s time, both internationally and financially,” he continued.

A Pennsylvania dilemma

Nowhere were the difficulties with white working-class voters more pronounced for Democrats than in Pennsylvania, the state of Biden’s birth and the one that solidified his 2020 win.

This year, Harris lost the state, Republicans flipped two House seats, and Casey faces a recount against his Republican opponent, David McCormick.

Casey’s struggle — even as Democrats triumphed in Senate races in Michigan and Wisconsin — serves as a striking illustration of the national challenges faced by the party and how essential factions of voters recoiled from its messages.

Casey, a senator for three terms, is the son of a well-liked former governor of Pennsylvania, Robert P. Casey Sr., and his family is a well-established name in state politics. For many years, conservative Democrats were commonly identified in the state as “Casey Democrats.”

The younger Casey secured his last election in 2018 by 13 percentage points. This year, the recount was initiated as McCormick surpassed Casey by less than half a percentage point.

In an interview, former Rep. Charlie Dent, R-Pa., reflected on the political shift that has been particularly vivid in his state.

More educated or moderate Republicans have been increasingly receptive to Democrats, while former culturally conservative Democrats have made a sharp move to the right in the Trump era.

“‘Pro-labor, pro-life, pro-gun’ — that used to be a significant part of the Democratic Party in Pennsylvania,” remarked Dent, who supported Harris this year. “It appears that demographic has firmly transitioned to the Republican side.”

Nevertheless, even some Democrats in Pennsylvania countered the national trends.

Rep. Chris Deluzio, a Democrat from western Pennsylvania, highlighted that he enhanced his support in Beaver County — a predominantly white, working-class area — this year, although he did not secure it.

He urged his party not to abandon the narrative of being “fighters,” advising fellow Democrats to adopt a clear economic message that addresses corporate dominance and advocates for unions.

“We absolutely need a national party that can succeed in the Rust Belt,” he concluded.