By Jazmine Ulloa

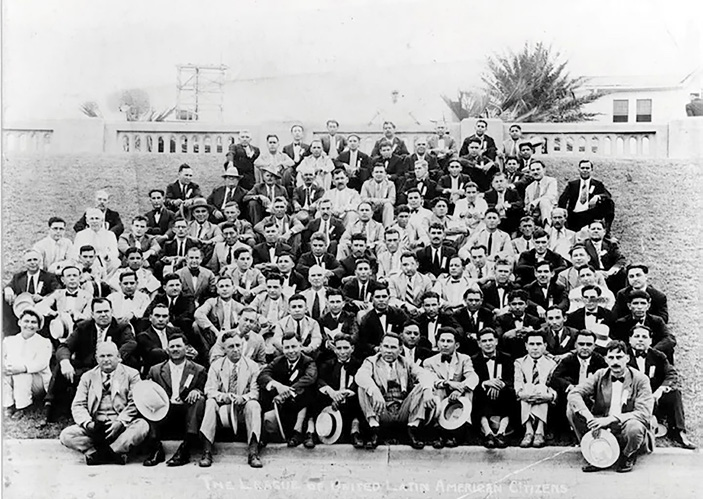

On a chilly and wet Sunday in February 1929, a gathering of stylish Latino men donned in suits and boater hats convened in a convention center in Corpus Christi, Texas, to establish a new civil rights organization for Latinos.

The majority of these men, numbering around 175, were Mexican American veterans who had fought in World War I. They returned home a decade prior to find a burgeoning Hispanic middle class in South Texas, where they played a pivotal role in the creation of three leading civil rights groups in the area.

These men sought to consolidate their organizations to form the League of United Latin American Citizens, or LULAC, with the aim of more effectively utilizing their resources to combat racial discrimination and to elect political figures who would advocate for their families and interests.

These ideas were revolutionary for their time. During this period, Jim Crow laws were prevalent, poll taxes disenfranchised many Black and Mexican American voters, and some dining establishments displayed signs prohibiting entry to dogs and Mexicans.

Nearly one hundred years later, as President-elect Donald Trump prepares to reclaim the presidency, LULAC is gearing up to take a stand against the incoming administration regarding issues such as proposed mass deportations, access to voting, education, and the social safety net.

In an interview, the group’s CEO, Juan Proaño, stressed that the mission of safeguarding Latino rights is more vital than ever. However, he acknowledged that LULAC is also grappling with electoral outcomes where a significant number of Latino voters, particularly Latino men, seemed to favor Trump, indicating they might not perceive themselves as part of the group’s struggle.

“We’re going to have to determine where to establish connections,” Proaño mentioned, describing the prospect of Republicans potentially controlling all three branches of government as “worse than my worst-case scenario.” He admitted that Trump had achieved better outcomes with Latino voters than previous Republican presidents: “I will give Trump credit where credit is due,” he stated.

In the coming weeks, Proaño indicated that his organization would analyze voter data to comprehend what factors led working-class Latinos to lean toward the right. This alignment with Trump occurred in spite of the fact that the organization’s political action committee had endorsed Vice President Kamala Harris in August, marking its first formal endorsement of a presidential ticket.

Even though the PAC’s leaders unanimously supported Harris, the group’s broader membership, comprising almost 325,000 individuals across 535 councils, showcases a wide array of political affiliations and ideological views. One council, based in the Houston area, protested the endorsement. Consequently, the organization’s bipartisan board will need to consider how to engage with the upcoming administration in a way that accurately reflects the diverse opinions within the Latino electorate and its own membership.

Proaño asserted that the stakes have never been higher: Trump and his supporters have garnered increasing backing from Latino voters, while at the same time, he noted that Republicans have attempted to suppress Latino voting power in recent years, partly through the propagation of conspiracy theories regarding noncitizens voting illegally. Proaño highlighted that these untruths laid the foundation for an investigation into voter fraud by Texas Attorney General Ken Paxton, which resulted in raids on the homes of some LULAC volunteers over the summer.

Perceiving the raids as part of extensive efforts by Republicans to restrict the activities of voting rights advocates nationwide, Proaño began to forge alliances with leaders of Black and Latino civil rights organizations months before the election. This month, LULAC announced its collaboration with a pro-democracy entity to challenge the voter fraud conspiracy theories and Paxton’s investigation.

“LULAC cannot navigate this alone,” Proaño stated.

An American promise

Proaño’s decisive position amid these complicated dynamics is consistent with his organization’s almost century-long legacy. LULAC has often been perceived as one of the more conservative Latino civil rights organizations, even while being involved in some of the most intense legal battles undertaken by progressives to desegregate schools and broaden voting rights for Mexican Americans and other Latinos.

Many former presidents and lifetime members of the organization noted the irony of the situation it currently faces.

Ruben Bonilla, 78, who served as president from 1979 to 1981, expressed sorrow that the raids in August aimed to label the group as “un-American,” despite its founding being rooted in American ideals.

“It is utterly appalling and shows the ignorance of public officials who fail to grasp our history,” he remarked regarding the voter fraud inquiry.

When the three civil rights organizations — the Order of the Sons of America, the Knights of America, and the League of Latin American Citizens — united to create LULAC in 1929, the influx of hundreds of thousands of Mexicans following the Mexican Revolution stirred anxiety among the Anglo American community in South Texas. To build political clout and counteract racism, the group urged Texans of Mexican descent to adopt an American lifestyle, become naturalized citizens, and learn English.

Over time, its members became perceived as more focused on reforming rather than overhauling American society, according to interviews with historians and some of its former leaders.

Benjamin Márquez, a political science professor at the University of Wisconsin-Madison who authored a book documenting the organization’s history, noted that while its members have never forsaken their Mexican or Latino backgrounds, they have consistently demonstrated loyalty to America, irrespective of whether the organization’s president was a Republican or a Democrat.

“Their aim was to eliminate racist prejudices in American society, and beyond that to mobilize votes, serve in the military, engage in elections, and run for office themselves,” he explained.

An unwritten past

Some historians contend that the organization’s activities have been mischaracterized as conservative when compared to Chicano groups that emerged later during the civil rights movements, which were more left-leaning and adversarial.

“The history of LULAC is largely unwritten, and many are unaware of its progressive strengths,” stated Cynthia E. Orozco, a historian and author of “No Mexicans, Women or Dogs Allowed: The Rise of the Mexican American Civil Rights Movement.”

Bonilla and his brothers, William and Tony, remembered that the organization became more politically active as Mexican Americans participated in “Viva Kennedy” clubs to rally support for John F. Kennedy in 1960, coinciding with the intensification of the Civil Rights Movement. William Bonilla, 94, who led in 1964, recalls initial registration efforts focused on encouraging Latino voters to settle their poll taxes. LULAC members drove around neighborhoods with loudspeakers, reminding residents to vote and transporting them to polling stations.

“It was from 8 a.m. to 6 p.m., all day long on Election Day,” William Bonilla recounted, recalling his blue Lincoln convertible used for these missions.

Proaño is now looking to leverage LULAC’s grassroots strengths while confronting the harsher aspects of its past. Throughout the 1950s, fierce competition for jobs and divisions between Mexican migrants and Mexican American laborers led the organization to initially back President Dwight D. Eisenhower’s mass deportation efforts. (This position was later reversed after the devastating impact on Mexican American neighborhoods and border regions.) Sometimes, tensions arose between Black and Latino civil rights organizations as they vied for limited resources.

Ruben Bonilla reflected in an interview that the 2024 election left him with conflicting emotions as he thought back on the organization’s struggles. He recognized that Republicans put forth a compelling argument regarding the economy, but expressed disappointment about the considerable number of people who supported Trump, a candidate who center-staged bigotry in his campaign and vowed to reinstate Eisenhower’s mass deportations.

Bonilla also observed another shortcoming in LULAC’s legacy: its historical exclusion of women from its ranks from the beginning.

“Hispanic men were hesitant to support a woman — it feels almost antiquated,” he remarked.