By Ben Sisario

“Quincy reached out to me.”

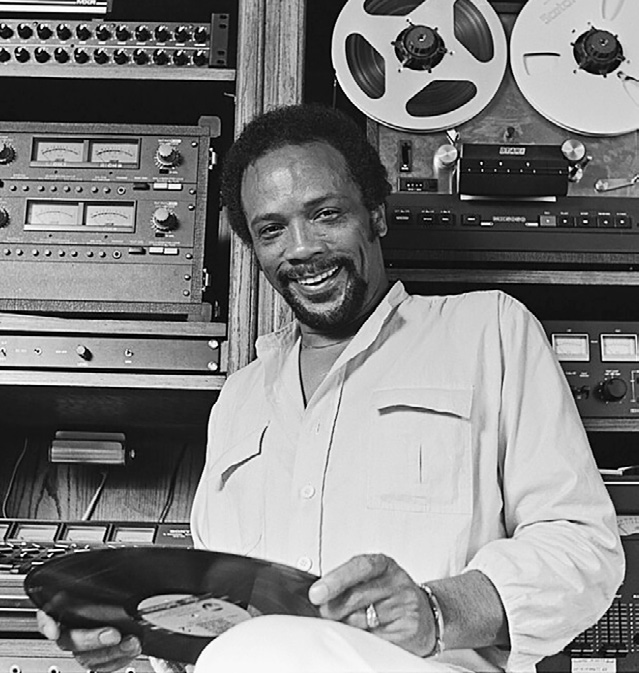

That line is the opener of the most captivating tales shared by some of the finest musicians globally over the past fifty years, as they reminisce about being called for recording sessions by Quincy Jones, the iconic producer whose work often hinged as much on casting talent as it did on capturing audio.

Eddie Van Halen received the call one day in 1982, to contribute a spectacular guitar solo to Michael Jackson’s “Beat It.” He opted not to take credit for it, but after Jackson’s passing in 2009, Van Halen described that session as one of the “dearest memories of my career.”

Greg Phillinganes, the synthesizer genius who started his journey with Stevie Wonder, received numerous such invitations as a sought-after session musician, lending his talents to albums led by Jones featuring Jackson, Donna Summer, and James Ingram, among others.

“Just receiving a call,” Phillinganes reflected this week, “was proof that you were deemed worthy to be there” — an initiation into an exclusive circle of both major stars and exceptionally skilled yet lesser-known musicians, all carefully chosen by Jones for their unique contributions to a project.

Jones, who passed away on Sunday at 91, was the master of a nearly lost art form of record-making that depended on collaborations among talented musicians under the precise guidance of a producer. For decades, he had a deep roster of the pop world’s top players available, and — in what could either be a career-defining opportunity or simply another studio session — would engage them to enhance a track with a guitar riff, or refine it with a synthesizer part, or anchor it with the perfect beat.

That framework of producers, studio musicians, and engineers collaborating in a large space, once fundamental to the pop industry, has steadily diminished with the advent of home recording and increasingly advanced technology, alongside reduced label budgets. However, in Jones, it had perhaps its greatest champion.

In his memoir, “Q” (2001), Jones devoted significantly more writing to the preparations for Jackson’s 1979 album “Off the Wall” — particularly selecting studio personnel — than he did to detailing its actual recording.

“I’ve always been fortunate to work with some of the finest in the industry,” Jones wrote, after listing the players, “and these individuals were not just a close-knit circle of friends but felt like my personal musical mafia: each was a black-belt master in his own field.”

A review of the credits on Jones’ albums across the years reveals a sort of rotating hall-of-fame of studio musicians. From the 1960s to the early ’70s, the credits featured jazz legends like Ray Brown, Toots Thielemans, and Herbie Hancock. By the ’80s, he leaned toward rock musicians; “Thriller” showcases four members of Toto, with its drummer, Jeff Porcaro, and guitarist Steve Lukather in prominent roles.

Jones was well along in his career before he ever identified himself as a producer. Born in 1933, he played trumpet in Lionel Hampton’s touring jazz band during the early ’50s and studied classical composition in Paris under Nadia Boulanger, who also taught Aaron Copland and Philip Glass. It was not until 1963, Jones noted, when he recorded Lesley Gore’s pop classic “It’s My Party” as an executive at Mercury Records, that he genuinely grasped what a producer’s role entailed.

“Prior to that,” Jones mentioned, “I never understood what a producer was or what they did.”

In reality, he had already taken part in several extraordinary albums by that point, arranging beautiful vocal jazz with Helen Merrill and vibrant big-band tunes on his friend Ray Charles’ LP “Genius + Soul = Jazz.”

By the 1970s, Jones had firmly established himself as a pop producer, and his background in jazz and film scoring provided him with extensive networks and immense respect among musicians.

“Quincy was the ultimate alchemist,” Phillinganes stated. “He understood the strengths and sensibilities of the musicians he selected. He knew who could do what, and he helped nurture that talent, bringing out the very best in everyone who collaborated with him.”

That approach was rigorous yet allowed for moments of spontaneity. Lukather received his first call at age 23, to play guitar on Jones’ solo project “The Dude” (1981). In an interview, he recounted how Jones provided him with a chord chart for the ballad “Just Once” — which Ingram, its vocalist, was another newcomer to “Q’s” world at the time — but allowed him to shape his own contribution, offering feedback along the process.

However, at every session, it was obvious to everyone present who was steering the ship. “Quincy was the general,” vocal arranger Tom Bahler mentions in “The Greatest Night in Pop,” the 2024 documentary about the sessions for “We Are the World,” the 1985 charity single that Jones produced.

In footage from that session, Jones stands authoritatively at the recording console, directing over 30 of the biggest stars of the era — including Bruce Springsteen, Bob Dylan, Jackson, Kenny Rogers, and Cyndi Lauper — as they contribute to the song’s chorus, intently watching Jones for cues and approval.

At times, the task involved reassuring the world’s most cherished recording artists that their performances were sufficient to meet Quincy Jones’ standards. During the recording of “We Are the World,” Dylan struggled with his solo line. “I don’t think that’s any good at all,” he expressed at one stage.

Jones removes his headphones and approaches. “You nailed it,” the producer assures him.

“If you say so,” Dylan responds with a chuckle, and they share a hug.