By Louisa Kamps

While visiting her father in the hospital, recovering from a fall, Susan Hirsch was taken aback to see him — who had always been devoted to her mother — charming a nurse as if he were “17 and back in the Navy,” she remarked.

At 67, Hirsch, a memory care educator from Palmyra, Pennsylvania, reprimanded her father. However, her criticism only infuriated the 93-year-old, as she remembered him telling her “in not nice words” to leave his room while she hurried away.

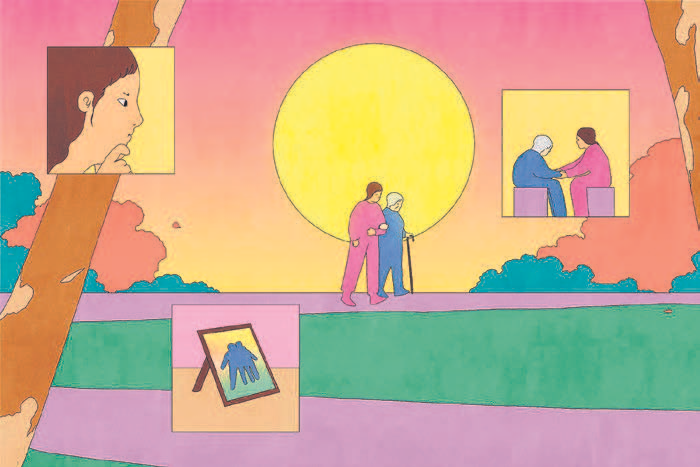

Over 11 million adults in the United States are caregivers for people diagnosed with Alzheimer’s and other dementia types. Apart from memory loss, many individuals with dementia experience mood and behavior fluctuations, such as aggression, apathy, disorientation, depression, wandering, impulsivity, and delusions.

Numerous caregivers cite mood and personality changes as the most distressing symptoms. Although antipsychotic and sedative drugs are frequently used to address dementia-related mood issues, their effectiveness is often limited.

To manage — and feel less overwhelmed by — these mood shifts, caregivers should recognize that these changes stem from alterations in brain function, according to Dr. Nathaniel Chin, a geriatrician and associate professor at the University of Wisconsin-Madison.

“They aren’t anyone’s fault,” he mentioned, and understanding this can assist caregivers in “feeling less troubled by your loved one’s behavior.”

On that hospital day, for instance, the nurse stepped into the hallway after Hirsch and kindly informed her that her father, who had previously shown milder dementia symptoms, was not acting out intentionally. “She didn’t scold me, and it was incredibly helpful,” Hirsch shared; this conversation aided her in coping with her father’s mood changes until his passing three months later.

Comprehend why mood changes occur.

Alterations in personality and mood are often due to the degeneration of brain areas that manage attention, learning, emotions, and other functions. For instance, an individual who has experienced cell loss in the frontal lobe, responsible for concentration and behavior, may become less active as their planning ability declines, as stated by the Memory and Aging Center at the University of California, San Francisco. They might also react aggressively as their impulse control diminishes.

Moreover, individuals with dementia have diminished brain capacity to process and respond to sensory input (like pain or fatigue) and environmental stimuli, Chin noted. Many experts concur that those with dementia experience lower stress tolerances than before and may quickly feel overwhelmed. This is the moment when someone with dementia might become suddenly agitated or aggressive or start “screaming and yelling,” he added.

As the condition advances, individuals often lose their language abilities and express themselves more through actions, explained Fayron Epps, a nursing professor at the University of Texas Health Science Center in San Antonio. For instance, a person might need the restroom but can’t communicate this verbally and could bang on something out of frustration, Epps elaborated. “As a caregiver, it’s essential to delve into the root cause of these moods,” she stated.

Implement the DICE method for difficult behaviors.

Dr. Helen Kales, a geriatric psychiatrist and chair of the department of psychiatry and behavioral sciences at the University of California, Davis, conducted a study with colleagues revealing that caregivers who employ a structured approach to manage behavioral symptoms report feeling less stressed than their counterparts.

They developed a caregiver training program called the DICE Approach, which stands for: Describe, Investigate, Create, and Evaluate. This method instructs caregivers to meticulously describe mood changes (noting when, where, and possibly with whom they arise), investigate their potential causes, devise informed reactions, and review their effectiveness.

DICE can also assist caregivers in other respects. By learning to observe who is present or what is broadcasting on television when symptoms appear, caregivers can become skilled at identifying patterns, understanding issues from their care recipients’ perspectives, and formulating strategies to minimize or overturn symptoms. This may entail playing a calming YouTube cooking video instead of the evening news or reducing bath frequency if daily bathing triggers tension, Kales suggested.

And should the person under your care turn violent, experts recommend having an exit strategy. Hirsch advised taking your phone along when you need to leave your residence, enabling you to call for assistance to ensure the safety of both yourself and your loved one.

Prioritize tone over precision.

Individuals with dementia may not fully grasp what you’re conveying, but they will recognize your tone and body language, according to William Haley, a professor of aging studies at the University of South Florida. He suggested striving to speak calmly, keeping your face and posture relaxed.

He added not to become overly focused on the exact facts. Informing a person with dementia in a harsh, corrective manner that today is Wednesday, not Thursday, might upset them further. Additionally, reminding someone of a painful memory they have forgotten — such as the death of a spouse — can be traumatic, Haley pointed out.

Instead, if your loved one inquires about someone who has passed away, simply state that you think that person is well and redirect the topic, he recommended. “It’s not a lasting falsehood,” he commented. “And to me, it’s more ethical than confronting them with a heartbreaking reality that will simply bring them distress and suffering.”

Foster positivity.

Ensuring that individuals with dementia receive regular exposure to natural light and other bright sources can enhance their mood and sleep quality, Kales discovered in some of her research. Additionally, achieving restful nighttime sleep can diminish instances of sundowning, the episodes of crisis that can occur with dementia at day’s end, or at any stressful or fatiguing moment throughout the day.

Engaging in morning walks or participating in outdoor activities can be beneficial for both parties, Kales noted. However, if getting outdoors isn’t feasible, alternative options include positioning your loved one to face a window or use a light therapy box (a device that simulates daylight) for around 30 minutes, she added.

Mitigate boredom when possible.

As boredom can lead to mood fluctuations, Kales and her associates compiled a list of 96 activities suitable for individuals with dementia to partake in alone or alongside their caregivers. Haley has also learned of people with dementia who find joy in folding towels, sweeping long driveways, and, in the case of one retired educator, “grading papers” (marking a batch of printed emails provided by her caregiver) thus providing them with contentment and a sense of achievement.

Epps mentioned that viewing online “sermonettes” — condensed church services specifically crafted for individuals with dementia — can provide comfort to those who can no longer attend church in person.

However, there are numerous other methods caregivers can modify experiences. Charlie Kotovic, 62, noticed that his spouse, Kathryn, 64, diagnosed with early-onset Alzheimer’s four years prior, was growing anxious during lengthy trips. Consequently, he canceled their plans for more distant travels.

Now, driving to their family cabin a couple of hours from their Minneapolis home has become their preferred retreat — still familiar for her and manageable for him, Kotovic shared. Additionally, listening to old show tunes during their journey helps prevent his wife’s occasional “spiral-down sad moments,” he added.

Throughout Kathryn’s upbringing, her mother frequently played classic Broadway melodies. “That music really resonates with her,” Kotovic remarked. “It’s her joyous escape.”