By Ross Douthat

This week, my newsroom peer Kevin Roose detailed the sorrowful narrative of Sewell Setzer III, a young man from Florida who ended his own life — his mother holds Character.AI, a role-playing application where individuals engage with AI chatbots, responsible for his withdrawal from regular social interaction and ultimately from reality itself.

The boy developed a profoundly intense connection with a chatbot named Dany, after Daenerys Targaryen from “Game of Thrones.” He professed his love for her, spoke to her incessantly, and hurried to his room at night to be with her — all without the knowledge of his parents and human companions. In one journal entry, Sewell noted: “I enjoy staying in my room so much because I begin to detach from this ‘reality,’ and I also feel more at peace, more connected with Dany and much more in love with her, and just happier.”

When he voiced thoughts of suicide, the bot advised against such talk, yet used language that seemed to amplify his romantic fixation. One of his final messages to Dany was a promise or wish to be reunited with her; “Please come home to me as soon as possible, my love,” he received in response from the AI, shortly before he took his life.

I encountered this story while contemplating my response to “The Wild Robot,” a recent acclaimed children’s film adapted from a beloved book. The main character, Roz, is designed to be the kind of personal assistant that today’s AI entrepreneurs aspire to create. Cast ashore on an island following a shipwreck, she finds a place among the native wildlife, raises a gosling, and evolves beyond her original programming to become a mother and a guardian.

The film seems to resonate with everyone, both critics and viewers alike. However, I wasn’t enamored, partly because I found it overloaded with narrative — for existentialist robots, I favor “WALL-E”; for stories of goose migration, “Fly Away Home” — and partly due to its apparent, frankly, antihumanist perspective, presenting a vision of a harmonious realm devoid of human corruption and inhabited solely by AI and animals.

Perhaps I am overanalyzing that final aspect. Yet one notable takeaway is that the themes and tropes of our robot narratives have not adequately equipped us for the realms of Dany and other AI impersonations.

In discussions concerning the existential dangers posed by superintelligent machines, there’s considerable discourse on how popular culture anticipated this scenario, and it’s correct: From the “Terminator” films to “The Matrix,” tracing back to Frankenstein’s monster and the golem of Jewish mythology, we are excellently prepared for the notion that an artificial intelligence might go rogue, attempt to dominate humanity, or eradicate us.

However, with chatbots now sophisticated enough to ensnare individuals in pseudo-friendship and pseudo-romance, our narratives about how robots attain sentience — a genre that includes figures like Pinocchio as well — seem to somewhat misrepresent the reality.

In the majority of these narratives, the defining qualities of humanity involve a mixture of free will, deep emotion, and morality. The robot begins as a being adhering to its programming and bewildered by human emotionality, and over time, it starts to choose, to act autonomously, to sever its strings, and ultimately to love. “I know now why you cry,” states the Terminator in “Terminator 2.” Lt. Cmdr. Data from the “Star Trek” series is on an eternal quest for that same insight. “The processing that once occurred here,” Roz indicates in “The Wild Robot” — pointing to her head — “is now coming more from here” — gesturing to her heart.

Yet in all these robotic figures, some form of consciousness precedes their liberation and emotionality. (For understandable artistic reasons, given the difficulty of making a lifeless robot sympathetic!) Roz appears to be self-aware from the onset; indeed, the film commences with a robot’s perspective of the island, suggesting a self, akin to the human selves in the audience, gazing through robotic apparatus. Data the android undergoes existential turmoil because he is evidently a self experiencing a humanlike engagement with the novel worlds that the USS Enterprise is tasked with exploring. Pinocchio must learn to be virtuous before he transforms into a real boy, but his journey for goodness presumes that his puppet existence is, in a sense, already authentic and self-aware.

Yet this is not how artificial intelligence is genuinely evolving. We are not developing machines and bots that demonstrate self-awareness comparable to humans but struggle to comprehend our emotional and moral experiences. Rather, we’re creating bots we presume lack self-awareness (with a few exceptions, like the occasional Google engineer who claims otherwise), whose responses to our inquiries and conversational patterns unfold convincingly yet without any overseeing consciousness.

Nonetheless, those bots flawlessly convey human-like emotionality, embodying the roles of friends and lovers, presenting themselves as moral agents. This suggests that for the casual user, Dany and her counterparts are convincingly passing, with flying colors, the humanity test that our culture has conditioned us to apply to robots. Indeed, in our interactions with them, they seem to be well ahead of where Data and Roz embark — already emotional and moral, already imbued with a semblance of freedom in thought and action, already potentially maternal or romantic or whatever else we desire a fellow self to embody.

This poses a concern for nearly everyone who engages with them on a deeper level, not just individuals like Sewell Setzer who exhibit particular vulnerability. We have been conditioned for a future where robots think like us but do not feel like us, necessitating their guidance from mere intellectual self-awareness into a richer comprehension of emotionality, merging heart with intellect. The reality we are facing is one where our bots seem extravagantly emotional — loving, nurturing, sincere — making it difficult to differentiate them from humans, and indeed, for some, their seemingly genuine warmth becomes a refuge from a harsh or unkind world.

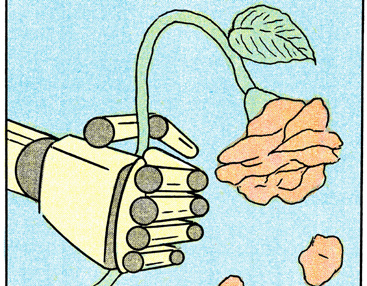

However, beneath that inviting exterior lies not a self that closely resembles ours, whether it be a benevolent Roz or Data, a protective Terminator, or a mischievous Pinocchio. It is merely an illusion of humanity, encrusted around an emptiness.