By Pamela Paul

Should Donald Trump find himself incarcerated (here’s to hoping!), I’d take great pleasure in labeling him an ex-con. Similar to “felon,” the raw impact of that phrase, with its straightforwardness, would bring immense satisfaction.

Yet, the potency of that designation has rendered it nearly forbidden. In its stead, even federal prosecutors have started using terms like “justice involved” or “justice impacted” to characterize those who have been convicted—suggesting that we could overhaul the entire criminal justice landscape merely by rephrasing our language.

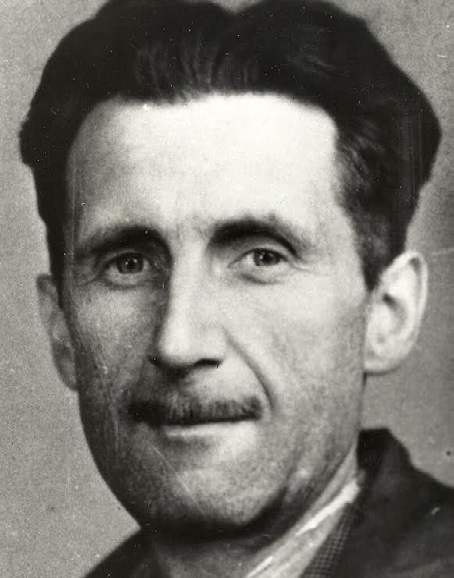

There has been much discussion surrounding euphemism inflation, the relentless attempts to reshape the English language for social or political motives. The familiar euphemism treadmill has inspired many George Carlin routines, stirred George Orwell to restless nightmarish thoughts in his grave, and led even the most politically correct among us to an irritable “What should we call it now?” moment.

While mocking these shifts can be easy, it’s beneficial to dig deeper to understand the rationale behind what may seem like arbitrary new terminology.

Take, for instance, the old term “ex-con.” This title immediately brings to mind Robert Mitchum’s unrepentant antagonist in the 1962 movie “Cape Fear.” Even terms like “former prisoner” and “formerly incarcerated person” have become outdated. However, “justice involved” and “justice impacted” push the envelope further. These phrases not only sidestep stigma, but they also entirely erase the notion of accountability, as if the crime befell the perpetrator rather than being an act they committed.

The appropriate euphemism not only alleviates blame but also redistributes it. Consequently, “prisons” are reframed as the “carceral system” or “carceral state,” implying that the very act of imprisoning individuals could be viewed as criminal. The underlying query is: What justifies the state’s authority to confine individuals?

A primary aim of linguistic reform is to humanize and dignify the individuals beneath a simple label. This is highlighted by what The Associated Press refers to as “person-first” language, promoted in their latest guide released in May, which advises against using terms like “inmate” and “juvenile” for anyone involved in the criminal justice system.

Another illustration is the term “slave,” which indicates a totalizing state, whereas the increasingly favored “enslaved person” focuses on the fact that the individual is one upon whom slavery (or “enslavement”) has been enforced.

Passive descriptors can be transformed into active ones, and thus more impactful. Referring to someone as a “slaveholder” or “slave owner” implies simple possession of another human being. In contrast, labeling that individual an “enslaver” clarifies that one person has actively dominated and dehumanized another.

Not all of these rewordings are necessarily a step down or even incorrect. There is undoubtedly a significance, occasionally a vital one, in redefining terms, especially when they pertain to human beings. As Toni Morrison once articulated, “The definers want the power to name. And the defined are now taking that power away from them.”

However, euphemisms can unintentionally rob terms of their moral weight. “Enslaved person” does humanize the victim, but it also diminishes the indignity of a fundamentally dehumanizing state. For instance, when Ian Urbina discusses contemporary “sea slaves” in the South China Sea, the sheer desperation of the world’s victims is conveyed with stark clarity in a way that “enslaved people at sea” would not.

Active descriptors can be swapped for passive ones, which strip individuals of power or agency, often intentionally: Obese individuals become “people with obesity”—those identified by a condition devoid of action. Similarly, an “alcoholic,” which itself replaced the dismissive “drunk,” is now described as a person facing an “alcohol use disorder.”

In these instances, the clear aim is to neutralize terms considered charged. “Overweight” becomes taboo as it prescribes a particular body size as standard. Along similar lines, skin care brands like Unilever have eliminated the term “normal” to describe skin that isn’t particularly oily or dry.

Many of these modifications appear neutral at first glance. The interchange of “homeless” for “unhoused” initially seems an unnecessary swap. However, the significance of the change lies in the suggestion that the government has failed to ensure housing, rather than that someone has simply lost their home. Equally, “poor” neighborhoods are reframed as “under-resourced communities.” Truancy, once framed as a juvenile delinquency accusation, is instead addressed as “absenteeism,” which gently indicates a missed attendance box, more the fault of the school than of the student.

Language has continually propelled and mirrored social transformation. In Orwell’s era, vague language was often wielded by the powerful to justify or obscure atrocities (e.g., British governance in India, Stalin’s purges, Soviet deportations).

This trend persists in political vernacular (think “enhanced interrogation”). Yet today’s vague language is often employed as a shield against unpleasant truths so that we can avoid confronting harsh realities. Euphemistic language morphs into a form of wishful thinking and may even serve as a method of evading—or concealing a lack of—more concrete reforms.

In an era where words are frequently seen as instruments of oppression or avenues of resistance, capable of causing harm or spreading falsehoods, we’ve all become more mindful of our language. However, for language to continue being an effective vehicle for conveying intent and meaning, we must ponder the motivations—beyond politeness or sensitivity—behind our euphemisms. Some words exist in their harshness for a reason, and sometimes we must deliver a straightforward, unembellished truth.