By Emiliano Rodríguez Mega

On Wednesday, Mexico’s Senate narrowly voted in favor of an extensive proposal to reform the judiciary system, effectively removing the final significant barrier to a measure that the nation’s president promised to advance before his term concludes at the month’s end.

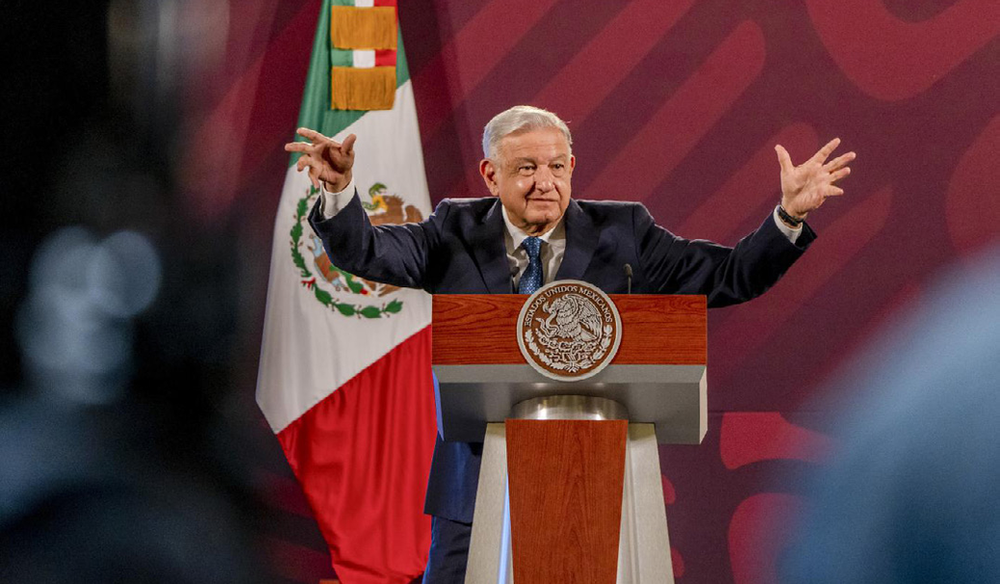

This outcome illustrates President Andrés Manuel López Obrador’s considerable influence and the strength of his party, following their substantial victories in the legislative elections in June, enabling them to advance some of the most controversial and extensive initiatives during his closing weeks in power.

The legislation would transition the judiciary from a system based on appointments, primarily reliant on training and qualifications, to one in which judges are elected by voters with minimal criteria for candidacy — resulting in the removal of 7,000 judges, from the Supreme Court’s chief justice to local court judges.

Having already passed the lower house of Congress last week during a lengthy session, the bill will now move to state legislatures, where a majority will be necessary for it to become law. López Obrador’s Morena party and its allies govern 25 of 32 state legislatures, so its approval is anticipated to be straightforward.

If enacted, voters could begin electing thousands of judges at the federal, state, and local levels as early as next year.

The discussion, which commenced on Tuesday, was briefly halted when a group of demonstrators, armed with megaphones and waving Mexican flags, stormed the Senate building, urging senators to reject the reform. The demonstrators pursued lawmakers to another location, where an opposition senator was attacked with gasoline. Police later dispersed the crowd using fire extinguishers.

Following a contentious session marked by accusations of “treason” and “deceit” among legislators, 86 senators voted in favor of the measure while 41 opposed it.

The administration argues that the reform is essential to modernize the judiciary and restore faith in a system riddled with corruption, favoritism, and nepotism. López Obrador’s successor, Claudia Sheinbaum, will assume office on October 1 and fully supports the initiative.

Nevertheless, the proposal has encountered strong opposition from judicial employees, legal scholars, investors, judges, students, opposition lawmakers, and various critics. López Obrador’s insistence on moving forward has kept financial markets on edge and sparked a diplomatic disagreement with the ambassadors of the U.S. and Canada. Even leaders within the Catholic Church have expressed that electing judges will not guarantee an improved justice system for Mexico’s victims of crime.

“What becomes of my 27 years of service? I started from the ground up,” remarked Sandra Herrera Benítez, a court clerk representing judicial workers in Monterrey, who participated in a strike last month alongside thousands of other federal court employees nationwide. “Now, to become a judge or magistrate, one must be affiliated with the president or some politician.”

Experiences from nations such as the United States and Bolivia, where citizens can elect certain judges, indicate that this could lead to greater politicization of judicial positions.

“Judges are influenced by the motivations created by elections,” explained Amrit Singh, a law professor at Stanford University and authority on rule of law. “The judiciary will be politicized to an unprecedented degree.”

López Obrador first proposed revamping the judiciary last year. Frustrated by the Supreme Court’s obstruction of some of his administration’s initiatives, such as undermining the electoral oversight agency or placing the National Guard under military command, he committed to instituting elections for judges — a strategy viewed by some analysts as retaliatory.

“The judiciary is in a hopeless state, it is corrupt,” he told reporters at that time, urging his supporters to secure large majorities in Congress to facilitate the reform and amend the constitution.

On Election Day, voters reinforced Morena’s control in the lower house, but left the Senate short of a supermajority. However, on Wednesday, Morena and its allies achieved the necessary two-thirds majority for passage when three opposition senators sided with the reform. Another senator, Daniel Barreda, missed the vote due to his father’s detention by authorities in southern Mexico, according to his statement to the media.

In the days leading up to the vote, opposition members claimed they faced threats, extortion, and bribes aimed at securing their support for the reform.

In recent weeks, protests and strikes have erupted across the nation in response to the proposed changes. Judicial employees and their allies have staged sit-ins to obstruct access to the lower house and the Senate.

Yet, there are also demonstrators advocating for the reform. Over half of the country’s business leaders are in favor of the proposal, according to Mexico’s chambers of commerce association. Polls commissioned by Morena suggest that about 80% of surveyed individuals believe reforming the judicial system is essential — although other surveys indicate that more than 50% of respondents are unaware of what the reform entails.

The situation has even created divisions within the Supreme Court. Justice Loretta Ortiz, appointed by López Obrador and identifying herself as a “founder of Morena,” stated on social media that the reform “will significantly ensure the access to justice that Mexicans deserve.”

Some experts believe it will take years to fully grasp the implications of the legislation.

“The president’s proposal is an untested initiative,” remarked Vanessa Romero Rocha, a lawyer and political analyst, adding that the effects of the overhaul will need evaluation over time given the lack of precedence. “The president’s main goal, as I perceive it, is to eliminate the long-serving judges who are deeply corrupt.”

Conversely, others argue that the current strategy may intensify the very corruption issues the government seeks to address.

“Dismantling the judiciary is not the solution,” Norma Piña, the chief justice of the Supreme Court, who opposes the measures, asserted in a televised address on Sunday. She also proposed an alternative plan to reform the system.

That alternative includes measures such as enhancing the transparency of judge selections to curb nepotism and emphasize merit, establishing independent disciplinary bodies, reinforcing local judiciaries — where corruption is more common — and improving state prosecutor offices.