By Harvey Araton

Bob Love, a key player for the emerging Chicago Bulls in the early 1970s who conquered a debilitating stutter post his NBA career by engaging in motivational speaking for the team, passed away on Monday in Chicago at the age of 81.

The Bulls confirmed his passing, stating he died in a hospital due to cancer.

Love’s stuttering, originating from his youth in segregated rural Louisiana, was so pronounced that he rarely engaged in interviews with the media throughout his 11-year NBA tenure, despite being the Bulls’ leading scorer for seven straight seasons.

“The reporters had deadlines — they couldn’t linger all night waiting for me to get my words out,” Love shared with The New York Times in 2002.

Called Butterbean in high school due to his love for butter beans, Love struggled to articulate even in huddles during timeouts, with teammate Norm Van Lier often stepping in for him.

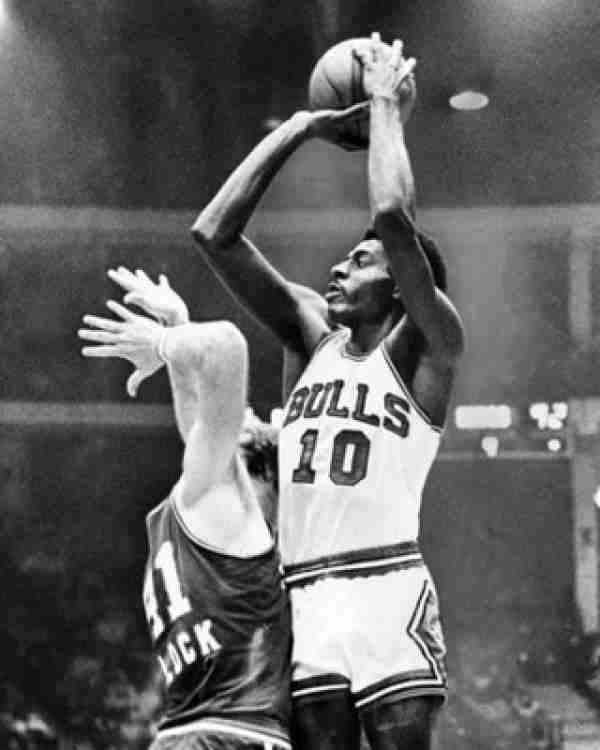

Standing at 6-foot-8, Love recorded a career-high average of 25.8 points per game in the 1971-72 season, showcasing a graceful jump shot that arched over his head. He participated in three All-Star Games and was recognized as second-team all-league twice. A well-rounded player, he was also named to the second-team all-league defense on three occasions and ranks as the Bulls’ third all-time leading scorer after Michael Jordan and Scottie Pippen.

Jerry Reinsdorf, owner of the Bulls, remarked in an interview for this obituary earlier this year that Love represented “a relentless defender who established high standards for competitiveness and toughness.”

Together with Love, fellow forward Chet Walker (who passed away in June) and guards Van Lier and Jerry Sloan, the Bulls secured stability for a struggling franchise that had considered relocating. Competing in the Western Conference, they faced losses in the playoffs for three consecutive years against the formidable Los Angeles Lakers featuring Wilt Chamberlain and Jerry West.

The Bulls narrowly missed reaching the NBA Finals in the 1974-75 playoffs. Love averaged 22.6 points and 6.6 rebounds in the conference finals against the Golden State Warriors but struggled with his shooting, making only 6 of 26 attempts in the critical seventh game. He felt that a better performance from him could have led the Bulls to victory and the championship.

A back injury curtailed Love’s career in 1977 while he was playing for the Seattle SuperSonics. Following a divorce, he faced financial challenges — his peak salary was $105,000 — and found it hard to secure employment, largely due to his stutter.

He took on work washing dishes and cleaning tables at a Nordstrom cafeteria. An executive, John Nordstrom, offered him a promotion with better pay contingent on his pursuit of speech therapy, which the company covered.

“All my life, I dreamed and prayed to communicate normally with others,” Love revealed in the 2002 Times article. “I would have sacrificed everything else to achieve that.”

In 1986, he began sessions with Seattle-based speech therapist Susan Hamilton Burleigh, meeting four times a week to work on breathing techniques and speech patterns.

“His stuttering was intense — there was a lot of pause and he often avoided eye contact,” Hamilton Burleigh noted in a phone interview. “He shared experiences about being a Black player who stuttered and discussed his work at Nordstrom, which he deemed shameful.”

Love recorded his everyday conversations and reviewed them in his sessions with Hamilton Burleigh. “He had tremendous motivation,” she recalled. “During one of our first meetings, he expressed, ‘I want to be a great public speaker.’ I replied, ‘That’s great.’ Yet soon he was speaking at various events around Seattle.”

Eventually, Love became Nordstrom’s health and sanitation manager, garnering media attention that caught the eye of Reinsdorf. In 1991, he rejoined the Bulls at the onset of their six-championship journey with Michael Jordan.

Reinsdorf had empathy for the challenges Love faced during his playing career and respected how he had “overcome numerous adversities in his life.”

As a representative of the Bulls, Love delivered speeches in schools, churches, and community centers. His growing confidence led him to campaign in 2003 for a City Council position in Chicago’s 15th Ward, though unsuccessfully.

In 2023, as a guest on a Nordstrom podcast alongside Peter Nordstrom, the president and chief brand officer, Love reflected on his post-NBA journey as “a testament to perseverance, of never adopting a victim mentality.”

Robert Earl Love was born on December 8, 1942, in Bastrop, Louisiana, a small town in the northeastern part of the state. His mother, Lula Belle (Hunter) Cleveland, was just 15 at his birth. He did not meet his father, Benjamin Love, until he was an adult.

To escape an abusive stepfather, he took refuge with his maternal grandmother, Ella Hunter, who provided support throughout his tough upbringing, exacerbated by his stuttering.

“I’d come home in tears, and my grandmother would comfort me,” Love recounted to the Times. “She would remind me, ‘Robert Earl, no one is perfect in this world. People often react harshly to things they don’t comprehend.’ ”

Constructing a makeshift basketball court in his grandmother’s cramped two-bedroom home, using a bent coat hanger as a hoop and his grandfather’s rolled-up socks as a ball, Love imagined himself as Bob Pettit, a star forward for the St. Louis Hawks.

He started as a quarterback at the historically Black Morehouse High School in Bastrop and later attended Southern University in Baton Rouge, Louisiana, to play football until basketball coach A.W. Mumford noticed his skills during a pickup game. Love finished his senior year averaging 30.6 points and 18.2 rebounds, becoming Southern’s all-time leading scorer in both categories.

With NBA teams hesitant to draft players from historically Black colleges like Southern, Love was chosen in the fourth round of the 1965 draft. He moved through the Cincinnati Royals to a minor league, back to the Royals, and then to the expansion Milwaukee Bucks before settling with coach Dick Motta’s Bulls.

Love’s first marriage to Betty Smith concluded in divorce in 1983. He is survived by four sons and two daughters from that marriage, four sons from other relationships, three brothers, two sisters, a stepchild, 18 grandchildren, six great-grandchildren, and his wife, Emily Collier, whom he wed in 2004.

Love was involved with the Stuttering Foundation of America and maintained occasional contact with Hamilton Burleigh, who once attended an award dinner where Love spoke. On that occasion, his speech was less than his usual fluid self.

“Here’s the reality of stuttering — there’s no definitive cure, it’s all about managing it,” she explained. “So I reached out to him after the speech and suggested, ‘We can always do a refresher course.’”

Recollecting his earlier insecurities from their initial sessions, she felt joy at his words.

“Susan, no,” he said. “If people have issues with my stuttering, that’s their problem. It’s no longer preventing me from doing what I need to do.”