By Brian Seibert

The vibrant sounds of Spanish guitar, the cries of a gravelly singer, and the resonating clapping and stamping — these noises could easily belong to a tavern in Andalusia, the birthplace of flamenco. Yet, this was the Metropolitan Opera House during a recent rehearsal of the new staging of “Ainadamar.”

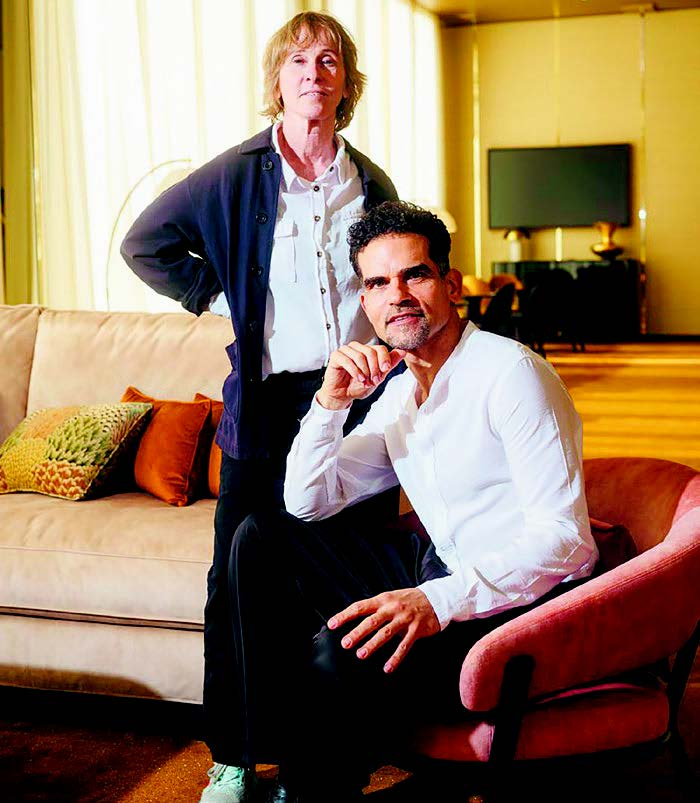

This one-act opera by Osvaldo Golijov, who hails from Argentina, made its debut at the Met on Tuesday. And beyond the flamenco sounds, the unique aspect of this opera house rehearsal was the presence of two choreographers, with Deborah Colker as the production’s director.

Since its first performance at Tanglewood Music Center in 2003, “Ainadamar” — a piece lasting 85 minutes focused on the Spanish poet and playwright Federico García Lorca — has seen numerous performances, including a Golijov festival at Lincoln Center in 2006. However, this version, which showcased at the Scottish Opera and Detroit Opera prior to its New York run, features the most dance seen in any of its adaptations.

“What Deborah has accomplished has astounded me,” Golijov remarked during a phone interview. “She unveiled a concept I hadn’t considered”: that the opera “can be continuously danced.”

Colker is recognized for her dance troupe in Brazil as well as her choreography for Cirque du Soleil and for overseeing the opening ceremony of the 2016 Rio Olympics. She has a background in music, having studied classical piano in depth as a child, but “Ainadamar” marks her inaugural experience as an opera director.

“I approach directing like a choreographer,” she stated after the rehearsal, explaining her straightforward method for the opera: gestures, movement, and dance. “This is my form of expression, yes, but it also aligns with what the music demands.”

Given that much of the music includes flamenco guitar and percussion alongside traditional orchestration, she felt it required an authenticity that she could not achieve on her own. This led to the involvement of a second choreographer: Antonio Najarro, a Spaniard whom Colker encountered a few years back while he was at the helm of the National Ballet of Spain.

“My task is to infuse genuine Spanish dance into the production,” Najarro expressed. “It’s not only about the movements, but about capturing the true soul of flamenco.”

The emphasis on flamenco in the opera is inherently tied to its theme: Lorca.

With a libretto penned by David Henry Hwang (translated into Spanish by Golijov), “Ainadamar” reflects on Lorca through the perspective of the Catalan actress Margarita Xirgu (soprano Angel Blue at the Met). In her final moments, while exiled in Uruguay, she reminisces about him, especially during the critical time he was labeled a communist and homosexual by the Falange, a fascist party, during the Spanish Civil War. “Ainadamar” is named after a spring in Granada, Spain, also referred to as the Fountain of Tears, close to where Lorca was believed to have been executed in 1936.

Born in Granada, the heart of flamenco, Lorca was an advocate for the art — mainly its cante jondo or profound song — and frequently integrated it into his poetry. His 1933 discourse on “duende,” the elusive force that evokes true emotion in flamenco, is arguably the most significant text ever crafted about this art form. Lorca’s connection to flamenco is so profound that a Granada festival introduces a new flamenco piece in relation to him every summer.

Golijov articulated that flamenco epitomizes “the very essence of Spain, which both nurtured and consumed Lorca.”

This is why Ramón Ruiz Alonso, the Falangist character who apprehended Lorca, performs in the style of cante jondo. At certain intervals, fascist propaganda broadcasts blend with flamenco percussion and footwork. Throughout an “Interlude of Gunshots,” which represents Lorca’s demise through an intense rhythm of clapping, stamping, and historical recordings of gunfire, members of the chorus collapse as if shot while Alonso sings a cante jondo sorrow.

The role is challenging, stated flamenco singer Alfredo Tejada, who portrays it at the Met, “because flamenco embodies complete freedom,” standing in stark contrast to fascist repression. However, he added, “I strive to uncover the character’s harshness and brutality through genuine flamenco purity.”

Colker observed that as she listened to the score, she envisioned dance in places where past adaptations did not. When Lorca (mezzo-soprano Daniela Mack) delivers an aria about Mariana Pineda, a 19th-century liberal martyr — the heroine from one of his earlier works, originally played by Xirgu — he recalls a statue of her that stands outside his window.

“I perceived this statue as a dancer,” Colker explained. Thus, she included a dancer in that moment — four in fact, each atop a table wielding a Spanish shawl. “There are four because it transcends reality,” Colker remarked. “It embodies a poem.”

When Xirgu attempts to persuade Lorca to flee to Havana, four shirtless male dancers swirl around him in his dream. (“They reach for Lorca all over — I adore this!” Colker exclaimed joyfully.) When Lorca declines to abandon Spain, he expresses his affection for the nation and its people as the chorus surrounds him, dancing and mimicking gunfire sounds with their handheld fans.

Later, as Xirgu passes away, a dancer adorned in a sweeping bata de cola dress pays homage to her from above a table. Xirgu’s funeral procession is accompanied by a flamenco dancer, arching gracefully like a matador.

Just about every performer in this staging engages in dance. Lorca flourishes a fan. Xirgu’s pupil Nuria (Elena Villalón), representing the emerging generation, sways to rumba beats. Xirgu employs theatrical gestures that are reflected and amplified by the female chorus.

“I wanted the audience to be unable to distinguish who is a dancer and who is a vocalist,” Colker added.

For Golijov, having his creation showcased at the Met holds significant meaning. The Met had commissioned him to compose an opera in 2007, but when it wasn’t completed by 2016, the project was scrapped. In the years leading up to this, other commissions had also fallen through as Golijov struggled with punctuality.

During his conversation, Golijov chose not to delve into this phase of his journey with the Met, citing only his pride in seeing this opera produced there. “It is meant to be here,” he asserted.

However, Golijov did elaborate on how “Ainadamar” was birthed from his challenges in adhering to timelines. Assigned by Tanglewood to create his first opera, he struggled to make progress as the deadline approached. A suggestion was made for him to seek Hwang’s assistance. Hwang inquired, “What do you cherish?” Golijov’s immediate reply was Lorca.

While Lorca sparked creativity for Golijov, he and Hwang confronted a dilemma: the Tanglewood opera commission aimed for an all-female cast of pre-professional vocalists along with renowned soprano Dawn Upshaw. After listening to recordings of the singers, Golijov was impressed by one woman’s rich, velvety voice, which inspired the notion that Lorca could be portrayed by a mezzo-soprano.

Golijov takes pride in presenting a Spanish-language opera at the Met. The prior year’s production of Daniel Catán’s “Florencia en el Amazonas” marked the first Spanish opera in nearly a century and only the third to be performed. “Spanish is such a beautiful language for opera, yet is so underutilized,” Golijov noted.

And, of course, Spanish was the tongue of Lorca. “Ainadamar” outlines a continuum of memory — of liberation, poetry, and affection — threading from Mariana Pineda to Lorca and onward to Xirgu and her students, a legacy that the opera itself perpetuates.

“We still require him,” Colker remarked, referencing the ongoing presence of prejudice and fascism.

“He remains among us,” Golijov stated. “I’m truly elated.”